Posture in Body-Friendly Scooter Design

A Scooter Design Perspective

In a previous design note, we looked at asymmetrical pushing and how easily it becomes the default on traditional kick scooters. We also touched on hip flexor strain as something that can quietly emerge over time.

But asymmetry alone is not the full story. Overall body position matters just as much. This is where the idea of body-friendly design started to take a more concrete shape. Asymmetry leads into posture, and posture is one of several areas that influence how body-friendly a scooter feels. In this note, we take a closer look at that posture-related area, without trying to cover everything at once.

From asymmetry to body position

On many traditional kick scooters, asymmetry is reinforced by posture. From a posture perspective, this can become demanding in several ways. The hips are often held in a rotated position, the supporting leg carries static load because the knee remains bent rather than extended, and the upper body tends to lean forward into a slightly hunched stance.

These posture-related factors strongly influence how body-friendly the ride feels over time, even before other aspects of the riding experience come into play.

Over short rides, this rarely feels dramatic. Over longer or repeated rides, it adds up. Not as a single problem, but as a combination of small stresses.

Allowing both feet side by side

One of the most direct ways to reduce forced asymmetry is allowing the rider to stand with both feet next to each other.

If the deck is too narrow, the feet do not fit naturally. That immediately leads to the idea of a wider deck.

This sounds simple, but… If it is too wide, pushing becomes awkward because the leg starts to hit the edge of the deck.

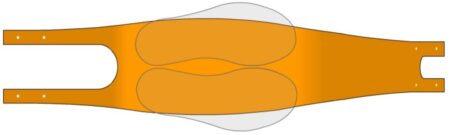

The way around this is not simply making the deck wider, but shaping it differently. A fuller, more pronounced center allows space where both feet actually stand, while keeping the sides slimmer where the pushing leg passes. In practice, more than half of the shoe width remains supported by the deck, even when the feet extend slightly beyond the edges.

This primarily reduces rotational load around the hips, and lowers the likelihood of sustained hip flexor strain caused by long-term asymmetrical stance.

Lower deck height and the standing leg

Reducing asymmetry alone is not enough if the rest of the body remains in a compromised position. Another key factor is how much the standing leg has to bend.

A higher standing height forces constant knee flexion. This increases static load on the knee joint of the supporting leg, and raises the risk of knee discomfort and fatigue over longer rides.

Lowering the deck reduces this. Pushing becomes easier. The standing leg can remain closer to a neutral position. Over time, this has a noticeable effect on fatigue.

Here, the design challenge becomes obvious. Lower deck height reduces ground clearance. Thinner structures reduce safety margins. Load capacity must still be maintained for real riders, not just ideal ones. These tradeoffs are not theoretical. They shape every millimeter of the structure.

With Boardy, the wooden deck made it possible to go thinner than we know any comparable structure could, while still carrying real loads. The solutions exist, but they always come with compromises. We will return to these in more detail later.

Upright posture instead of bending forward

Symmetry at the feet does not help much if the upper body is still folded forward.

Allowing a more upright posture reduces continuous flexion in the lower back and decreases strain in the lumbar region that can build up when riders have to lean forward for long periods.

Allowing a more upright posture requires a handlebar that can be set higher. That introduces its own design questions. Stiffness. Control. Load on the steering tube.

Still, if the rider has to bend to reach the bar, the body compensates elsewhere. Upright posture is not a comfort feature. It is part of keeping the whole system balanced.

Body-friendly is more than three features

In this design note, we have touched on three closely related aspects of body-friendly scooter design:

- Standing side by side.

- Lower deck height.

- More upright posture.

None of these alone defines a body-friendly scooter. And these are not the only factors that matter. What makes a difference is how these elements work together. Together, they reduce the need for constant compensation during riding.

There are other factors that play an important role as well. Overall weight. How much vibration reaches the joints. How much attention the road surface demands from the rider. These topics are closely connected to what we discussed here, but they deserve their own space. They will be explored in future design notes.

For now, this note marks a shift in thinking. From observing asymmetry and strain, toward actively designing against the conditions that create them.

Not by eliminating every limitation, but by choosing which ones the body should no longer have to work around.